Too many Americans live paycheck to paycheck. This researcher has some ideas to help

Published in Business News

For all the change constantly happening in and around the Magic City, many Miamians feel stuck.

More than half of Miami-Dade’s population lives paycheck to paycheck. They’re spinning their wheels, moving from one day to the next, hoping they avoid the health emergency, job loss, car accident or hurricane that would push them over the financial cliff.

They’re surviving, but not thriving. Milestones like homeownership that once felt attainable are out of reach. Now, it’s a matter of making rent.

That dynamic is playing out across the country. It’s amplified in South Florida. Post-pandemic, the region saw a flood of outside money drive up local income inequality and, with it, prices — especially for housing.

Meanwhile, locals’ paychecks haven’t kept pace. They’re struggling to save, struggling to invest — in stocks or businesses or themselves — and struggling to get ahead.

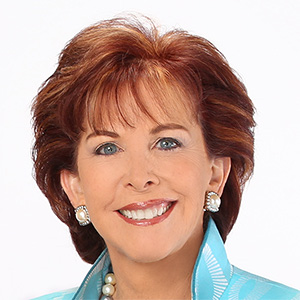

Heather Cameron is the Michael B. Kaufman professor of practice in social entrepreneurship at Washington University in St. Louis. She just received nearly $1 million in grant money to figure out how to improve economic mobility in American cities.

The Miami Herald sat down with her recently to find out more.

Below is an edited version of a 40-minute interview with Cameron. It touches on why it’s harder to get ahead today than it was decades ago, the value of money, a different way to think about housing, and what can be done to make life healthier and more affordable for everyone. The Herald encourages readers to listen to the full interview here:

Q: How do you define economic mobility?

A: Economic mobility is basically just the changing of your economic status over time. It’s a key part of the American Dream; the idea that kids can do better than their parents, that we’re all improving as a society, and also that if you’re born a child into poverty, you don’t necessarily have to stay there.

Q: How mobile do you think the United States is today?

A: The Federal Reserve System has noticed that, for the last 30 or 40 years, economic mobility is stagnating in the United States.

Why is this happening? It’s because of the way our economy has changed dramatically since the 1970s.

Q: What are some of those changes?

A: After World War II, there were huge investments and growth in the American economy, and most of the money flowing in the economy was actually being used for what we would call productive things. It was industrial capitalism. People made investments into factories. The factories grew bigger. They made more stuff. They got profits from that.

Then, the economy moved more into what we call financial services. The banking system, the insurance system and real estate took over more and more of the economy, and people could make money just by basically owning stuff, not by making stuff, and by charging other people to use it.

Over the last 30 years, people who own assets, whether that be stocks and bonds or real estate, they’ve been getting a much better return on owning that stuff than people who work. And that leads to income concentrations at the top and at the bottom, and it makes it very hard for the people at the bottom to jump up, because the ladder is expanding.

Q: So your research will examine community wealth building. What is that?

A: Community wealth building is the idea that, if a community controls more of its assets, and more of the money that’s generated in the community stays there, then it will do better.

Q: What are some examples of community wealth building strategies you think could be successful or have been successful?

A: Community banks. That’s a publicly owned or community-driven bank, and its goal isn’t just maximizing profits. They’re covering their costs, but they’re focusing on investing in local businesses and the needs of residents. So, for example, standing up kindergartens or grocery stores in neighborhoods that need them.

Another strategy is making workers “worker-owners.”

Q: How does that work?

A: Right now, there’s this huge transfer of wealth happening because so many baby boomers who built up businesses are retiring and realizing that there aren’t necessarily people who want to buy their business. And so (some of my research is) going to be looking in Kansas City for different businesses where owners are wanting to retire. They don’t want to see their businesses sold for scrap, but rather to be sold to their workers. Then the workers will have the opportunity to build assets through owning part of the business.

We’ll also focus on so-called “anchor institutions” — universities, health centers, large employers in the area, organizations that are committed to that city — and come up with strategies for them to be able to buy more of the goods and services they need locally and keep that money flowing in the local community.

Q: Housing is a big issue here in Miami. Most people here are “rent-burdened” and struggle to make ends meet. Some of your research will focus on strategies to make housing more affordable and attainable. Tell me about them.

A: Normally when you buy a house, you’re not just buying the house. You’re buying the land underneath it. Because of that, the price is obviously a heck of a lot more than if you were only buying the use of the building.

Shared equity models are basically a way for low-income people — who don’t have the assets available to put down a big down payment but who do have the money to make monthly rent payments — to have stable housing.

Community groups, like nonprofits, would do something called a “community land trust,” which is basically a way to avoid gentrification. Locals who want to stay where they are but who can’t afford to buy the houses, or who are having the houses bought out from under them, can come together and say, “Hey, we should protect our neighborhood by turning it into a community land trust.”

People are able to buy into (the housing on that land), but the amount of upside that they get on their investment in a house on that land is capped. The advantage is that they can get a house and have all the nice things about being in a house and having a nice neighborhood. But, because it’s not floating on the free market, the amount of upside they get is capped, because they would sell [the house] back to the group they bought it from.

The goal is to make it easier for people to get access to housing. And so the way they do that is to keep it permanently affordable and off the private market.

Q: So, if I understand correctly: nonprofits and/or individuals in a community form a land trust. That trust buys a plot of land. Let’s say the trust, which is governed by a community board, decides to construct a building on that land. People buy units in that building, or a house on that land, but there’s a limit to how much they can resell them for, and that keeps the housing affordable?

A: Right. There’ll be rules about what your income has to be in order to buy in. We can get more people into high quality, stable housing, if the goal is not just capital appreciation on the house.

Q: Especially in Miami, housing is often purchased explicitly for its appreciative value. People want the value of their homes to go up as much as possible, which goes against the concept you just outlined. So how have people received this idea?

A: To make our economy work better for people requires people to think differently about what money is for and what the economy is for and what housing is for. There’s a lot of people who are currently renting in a very insecure way, spending more than a third of their income on rent, which causes problems for their families, for their kids, which causes extra stress.

If you told those people, who are hard-working and who have access to money to pay rent, “you could buy this studio apartment that you’re living in. You’ll be part of a housing community where there are rules, but you’ll help shape those rules. You’ll have stability — what you pay isn’t going to change in an unexpected way just because the landlord said so,” they would jump at that.

And if they have extra money, then great, put it in the stock market. That’s where we should be investing money. In the American economy. That would be my argument as an entrepreneur. Let’s go build stuff to make more profit. Let’s go create more innovations. Not just, I buy a house, you buy a house, we trade and we ‘make’ money.

Housing can be seen not just as a speculative investment, but as something we need to have safe and healthy neighborhoods. We don’t want people changing homes three times in one school year. We don’t want neighborhoods that are broken down because the neighbors don’t trust or know each other. We want places that are clean and healthy and walkable and good for families. Where people can build up as they go, rather than needing to have a whole bunch of money just to jump in and then be afraid that if they miss one payment, it’ll be taken by a bank — which doesn’t work to help them keep their home but is interested in selling it to the next guy.

Q: Practically speaking, how do these cooperative projects get off the ground? Who makes them happen?

A: Lots of different people. There are banks and investment funds that do mission-driven finance. But even the big hedge funds are talking about the value of shared ownership and employee ownership as a way to unlock value for American companies, to get more people in the owner’s box, getting them committed to improving companies because they’re owners.

In terms of the housing stuff: Generally, neighborhood organizations work with city governments or philanthropic organizations to stabilize neighborhoods and create opportunities for people to get into homes while avoiding gentrification. They come together to get a loan against the value of the land, and then they put houses or multi-family units on [the land]. Then, they’re able to service that loan in perpetuity by the payments of the people who live there. Lots of banks have worked to help create these community land trusts because they see the value in stable neighborhoods for the greater community.

And people are starting to do this in commercial real estate, too. There’s a project in Portland where a community development fund bought a mall in a low-income area and turned it into a place where local small businesses could have their stores. People in the neighborhood and surrounding zip codes had the opportunity to buy into the community fund, and now they get a share of those rents. It’s a question of how you get the money together. Their model was a whole bunch of people paying a small amount, plus initial startup money.

It’s just smarter ways of putting money to work. These things don’t really require a huge amount of money. It’s more technical know-how and willingness to learn from these examples, which are all over the United States, but not yet enough. We can do even more.

(This story was produced with financial support from supporters including The Green Family Foundation Trust and Ken O’Keefe, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners.)

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit at miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments