No campaign? No problem. Inside California political elites' shadowy spending

Published in Political News

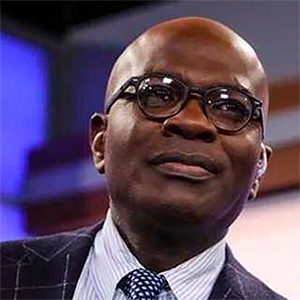

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — California state Sen. Mike McGuire, a Santa Rosa Democrat, is a die-hard San Francisco 49ers fan.

During his first speech as Senate president pro tempore in early 2024, McGuire gave a shout-out to his beloved team, who were days away from facing the Kansas City Chiefs at the Super Bowl.

His late grandmother “would be more excited that the 49ers are heading to the Super Bowl than me being up here today,” McGuire joked to laughs and applause.

“So I think we need to do a ‘Go Niners,’ everybody.”

A few days later, McGuire attended the game in Las Vegas. He paid for the tickets not out of his own pocket, but through a ballot measure committee called “Progress for California.”

The committee spent $40,000 for tickets, meals, lodging and transportation for a three-day stay in Las Vegas during the event, according to campaign finance records, paying Super Bowl beer sponsor Anheuser-Busch directly. The company also gifted McGuire ticket packages worth $33,750.

A campaign spokesman for McGuire said the trip was for a fundraiser held with his predecessor, former Senate pro Tem Toni Atkins.

In the two years since he opened the account, McGuire’s “Progress for California” ballot committee has amassed more than $850,000 in political donations from labor unions, tribes, businesses and other political action committees

But despite its name, it has yet to donate to any ballot measure.

The arrest and indictment of Dana Williamson, a former top aide to Gov. Gavin Newsom, cracked open a window to Sacramento’s campaign finance ecosystem, showing the sometimes questionable ways that lawmakers, lobbyists, consultants and interest groups use accounts to trade money, time and access.

A Sacramento Bee review of more than 100 accounts and lobbying records reveals how two types of accounts in particular – ballot measure committees and campaign accounts held by ex-lawmakers – are commonly used to shore up political connections and help elected officials live large, while spending little, if anything, on campaigns those accounts were ostensibly designed to support.

Williamson, Newsom’s former chief of staff, pleaded not guilty in November in a scheme to enrich her friend Sean McCluskie, a longtime deputy to former Attorney General Xavier Becerra, using money funneled from one of Becerra’s dormant campaign accounts. McCluskie and another lobbyist pleaded guilty; Becerra said he was unaware of what was happening and cooperated with federal investigators.

The Bee’s analysis of campaign accounts controlled by current and former elected officials, including dozens like the one used to steal from Becerra, reveals the price to get a state lawmaker’s ear for an evening or a weekend – and it’s not cheap. Special interests often donate tens of thousands of dollars to lawmakers and gain access to private fundraisers at high-end resorts and other exclusive events.

After years of lax oversight from the Fair Political Practices Commission, some elected officials exploit loopholes to cozy up to special interests. Others push legal and ethical boundaries to set themselves up for a career in the private sector after term limits. This type of political spending is legal under California law.

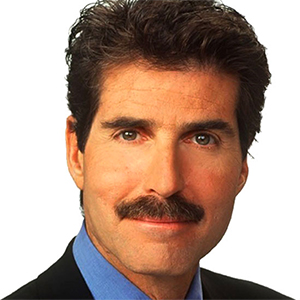

“Money in politics is kind of this perverse game where both parties are guilty of the pay-to-play,” said Sean McMorris, a program manager for California Common Cause, a nonpartisan group that advocates for democracy and good governance.

Campaign finance loopholes allow players to trade money and influence without breaking the law, he said. “So they can say, ‘Hey, I’ve done nothing wrong,’ and they often do. It patronizes the heck out of the public because we’re not stupid.”

The review of campaign finance records follows recent reporting by The Bee and other news outlets about questionable spending by state lawmakers and other California elected officials, including Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara and Assembly Republican Leader Heath Flora.

Ballot measure committees fund much more

McGuire’s ballot measure committee shows how special interests are able to funnel tens of thousands to the very lawmakers they spend months lobbying. In the same way that federal PACs can raise unlimited funds from special interests, these campaign accounts have few restrictions on how much they can raise from a single source.

Top donors to the committee include Smart Justice California, a criminal justice advocacy group, and health care company DaVita, which have each given more than $100,000 since 2024.

Many lawmakers who control ballot measure committees use them to raise money to sway voters on ballot propositions. But campaign finance records show that since creating the account in late 2023, McGuire has not used the committee’s money on any actual ballot campaigns.

Instead, his “Progress for California” committee has been used primarily as a vehicle for fundraising: collecting large checks from special interest groups and spending thousands to attend fundraisers – including the Super Bowl event – and dinners.

McGuire did cut checks totaling over $150,000 to the ‘Yes on 50’ campaign in 2025 as the redistricting measure went to voters – however, those donations did not come from Progress for California, but another campaign account he was using to run for a higher elected office.

When asked about the committee’s spending, a spokesperson for McGuire’s campaign said the Super Bowl fundraiser was held alongside Atkins, who for years held fundraisers at the NFL championships. Campaign records show Atkins’ own ballot measure committee spent more than $150,000 to host the 2024 fundraiser. She also dropped $345,000 into various ballot measure campaigns in California and Nevada that year.

The Bee reviewed 90 active ballot measure committees controlled by sitting or former elected officials and found that these accounts are funded almost exclusively by special interests, which cut checks worth thousands – sometimes tens of thousands – of dollars. The money is often given to attend fundraisers at entertainment venues or luxury resorts.

In exchange for a “suggested donation” to the committees, trade organizations and other businesses and industry groups that regularly lobby the legislature can send a representative to rub elbows with a host lawmaker for an evening or weekend away from the Capitol.

“There’s no quid pro quo most of the time. It would be illegal,” said McMorris with California Common Cause. “But everyone knows how the game is played. It’s kind of a wink-and-a nod thing.”

Since 2024, lawmakers have hosted fundraisers at Beyoncé and Taylor Swift concerts, Disneyland, Las Vegas and lavish resorts such as Pelican Hill in Newport Beach. Many lawmakers also use their ballot measure accounts to pay political consulting fees.

Because candidates and elected officials are not required to report certain details about these fundraisers, few specifics are known about who attends and whether potential legislation is ever discussed in private.

State laws prevent registered lobbyists from making political donations, but no rules prohibit a company or interest group from donating a large sum for access to an elected official’s fundraiser, and then sending their lobbyist to the event.

Lobbyists and other “moneyed interests” know that donating to an elected officials’ campaign account – or accounts – is a way to “curry favor,” McMorris said. Politicians know it, too, “so those are the first people they reach out to for campaign contributions.”

The Bee’s analysis found most lawmaker-controlled ballot measure committees do spend money to either support or oppose ballot propositions. But some committees have spent upwards of $100,000 on fundraisers paid for, and attended by, the same businesses and association groups that lobby the Legislature while spending little, if any, money trying to reach their voters about a particular issue.

In early 2025, Assemblymember Blanca Rubio, D-Baldwin Park, reported spending north of $63,000 on a three-day trip to New Orleans that fell over Super Bowl weekend in that city. Rubio used the ballot measure committee to pay for travel and meals for herself and three members of her household, which she expensed as related to a fundraiser. She also used the account to make a $6,000 purchase at the Apple Store and to pay for Clear, the airport clearance service.

And in an unusual move, Rubio has used her ballot measure committee to pay a nearly $4,000 monthly salary to a campaign worker. The employee, Hilda Escobar, also works as Rubio’s legislative scheduler, a job for which she earns an annual salary of $107,868.

Rubio’s campaign did not respond to the Bee’s questions about her ballot measure committee spending or the nature of Escobar’s work on it.

Her sister, Sen. Susan Rubio, D-Baldwin Park, has spent more than $40,000 from her own ballot measure committee for two small fundraisers at a wellness resort in Tucson, Ariz., since last year.

Since taking over as chair of the Senate Insurance Committee in 2019, her ballot measure committee has taken at least $193,000 from industry players, including Allstate, the American Property Casualty Insurance Association and the Personal Insurance Federation of California Agents.

While Blanca Rubio did use her ballot measure committee to give $25,000 in support of Proposition 50 last year, Susan Rubio reported no spending on ballot measures or related items like ads or mailers.

A spokesperson for Sen. Susan Rubio said she “has always acted with the highest level of ethical and moral integrity, placing the interest of consumers and residents above all, and voting on issues regardless of who has contributed to her campaigns.”

State lawmakers representing Orange County have a history of hosting large fundraisers at Disneyland – a tradition that Assemblymember Avelino Valencia, D-Anaheim, has continued.

In 2024, most of the money spent by his “Golden State of Mind” ballot committee – about $150,000 – paid for a fundraiser at the theme park, a huge and influential economic force in Valencia’s district.

“Golden State of Mind” has raised more than $480,000 over the past two years, mostly from groups like the California Apartment Association and PACs controlled by public employee unions, health care and insurance companies, and other lawmakers.

A fraction of the money in that account has gone toward advocating for ballot propositions – Valencia spent $22,000 last fall to help pass Prop. 50, and in 2024 he donated $2,500 to oppose Huntington Beach’s voter ID proposal.

Valencia has not filed reports for most of his ballot committee’s spending in 2025, though his campaign confirmed he hosted another Disneyland fundraiser last year.

The fundraisers “followed all applicable campaign finance rules,” said Derek Humphrey, a spokesperson for Valencia’s campaign. “The committee produced direct mail and digital billboards in support of Proposition 50 (in 2025) and plans to be active again in 2026.”

Humphrey also said Valencia made an additional in-kind donation for Prop. 50 mailers that has not yet been reported.

Former lawmakers keep accounts open, work in lobbying

Campaign finance law allows lawmakers to raise and spend large amounts of money through ballot measure committees that require no link to an actual ballot measure. The same is true for campaign committees held by lawmakers who have left office – a real campaign isn’t necessary.

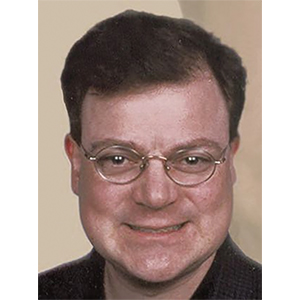

For the past 17 years, former Democratic Assembly Speaker Fabian Núñez has transferred the money he raised in office to new campaign accounts at a regular interval – for Senate in 2010, Treasurer in 2014, Treasurer in 2018, Treasurer in 2022 and Treasurer in 2026.

In that time, he has never again run for office, instead using the balance of the accounts to give hundreds of thousands of dollars to sitting legislators.

The pattern began shortly after Núñez termed out of office in 2008, when he became a partner at a lobbying firm in Sacramento. Soon after he was hired at the firm, Núñez transferred $5 million from his existing campaign account to a new one – Friends of Fabian Núñez for Senate 2010.

Months later, that account gave $3,672 to the campaign account of sitting Assemblymember Ricardo Lara, according to campaign finance records, and a month later, $1,000 to the account of then-Assemblymember Kevin McCarty.

Registered lobbyists are not allowed to make these kinds of contributions, but no rules prevent partners and owners of lobbying firms from doing so. Over the years, Núñez has given over $1.3 million to political candidates and their causes, including $228,000 during the first six months of 2025.

Núñez didn’t answer directly when asked via email whether he really plans to run for Treasurer this year.

“Mr Núñez is passionate about the issues that matter to Californians and is continually looking for another opportunity to serve them,” said Núñez’s spokesperson, Steve Maviglio. “He also actively contributes to causes and candidates that share his vision.”

Campaign finance records show Núñez gave $6,500 to help elect Maviglio to the American River Flood Control District Board.

In addition to Núñez’s account, The Bee reviewed dozens of other accounts opened for 2026 and 2030 races, and found that in many cases, these accounts belonged to former lawmakers who use them to hold and spend money raised during their time in office – not to run for the seat in question.

The accounts rarely spent money on campaign-related expenses – like consultants, polling, mailers or other voter interaction – and almost never raised additional funds. Instead, some former lawmakers have used them to further their careers in lobbying and public affairs.

“It’s essentially a lifetime slush fund for former elected officials,” said Dan Schnur, a former chairman of the Fair Political Practices Commission who is now a political science professor at USC, Pepperdine and UC Berkeley.

“Donors give you money for a specific reason for a specific election, and once you decide not to seek office anymore, you’re free to spend that money however you like, regardless where it came from and the reasons that a donor may have given it.”

Núñez didn’t just spend his money on campaign contributions. As a founder and managing partner of the global consulting firm Actum Strategies, he also gave money to charities with ties to his firm.

An analysis of Núñez’s accounts show at least two instances of overlap between organizations he has donated campaign funds to and those that have been clients of Actum Strategies. In 2019, he gave the Anti-Recidivism Coalition $12,500. At the time, his son was the organization’s policy director. In 2023, the Anti-Recidivism Coalition became a client of Actum’s and contracted with the firm in 2024 and 2025.

One of Actum’s largest clients is AltaMed Health Services Corporation, a federally qualified network of community health centers in Los Angeles. They became clients of the firm after years of donations from Núñez’s campaigns. From 2023 to 2025, the organization spent close to $700,000 on Actum’s services. At the end of 2024, Núñez gave $150,000 to the fundraising arm of the corporation, AltaMed Foundation.

“Former Speaker Núñez has a long track record of charitable giving from his accounts in compliance with state law, particularly to those causes like health care and human rights that he is passionate about,” said Maviglio. He added that the AltaMed Foundation’s board is separate from the corporation.

There are other examples of lawmakers leaving public office for lobbying roles, but keeping their accounts open and spending from them.

Former Democratic assemblymember Tom Daly, who left office in 2022, spent $33,000 in 2025 from a “Daly for Insurance Commissioner 2026” account. Daly currently is a partner at the lobbying firm Clear Advocacy. He is not currently running for Insurance Commissioner.

The largest expense from his account was $14,000 in “civic donations” to the Independent Voter Project, an organization that hosts an annual conference with legislators and lobbyists in Maui. Daly made a similar “civic donation” of $12,500 to the IVP in 2024, and was listed by the organization as one of its 2024 attendees on behalf of Clear Advocacy. He is not a registered lobbyist for the organization, though his wife, Debbie Daly, is. Other expenses from 2025 include thousands of dollars spent on campaign contributions to sitting legislators.

Democratic state Senator Bill Dodd left office in 2024 and now runs a legislative and public affairs service firm, Dodd & Chaaban Strategies LLC, where his former chief of staff, Ezrah Chaaban, is a registered lobbyist.

Dodd began 2025 with about $1 million in his “Dodd for Lt. Governor 2026” campaign account, although as of January he was not campaigning for the office. He did use some of the balance in 2025 to pay $7,200 for six people to attend the BottleRock Music Festival in Napa, and over $3,200 for airfare for four people to attend the ritzy Protem Cup golf fundraiser in San Diego. The records did not say who attended the events with him and his wife.

Former assemblywoman Autumn Burke was also apparently considering a run for lieutenant governor this year. She spent over $450,000 out of her “Autumn Burke for Lieutenant Governor 2026” account in the years after she left office in 2022, on conferences and political contributions.

She is currently transferring the $111,000 in that account to an “Autumn Burke for Insurance Commissioner 2030” account. Burke has been a registered lobbyist at times for Axiom Advisors and started a new political strategy company, Revan Consulting Group, in April 2025.

When reached for comment, Burke said her contributions have nothing to do with her role at lobbying firms and that she is “seriously considering” running for the position of Insurance Commissioner in 2030.

According to campaign finance records for her lieutenant governor account, in the latter half of 2023, Burke also donated $25,000 to her own charity, BIWOC on K, for which she is the president. The organization puts on talks and networking events for women of color in Sacramento, and solicits sponsorships from companies like AT&T and the California Faculty Association.

Burke said she doesn’t derive any income from the charity and didn’t see why donating money to the cause would be a problem.

McMorris said even if a charitable contribution doesn’t incur a monetary benefit to a candidate, “it could benefit them in other ways, like name recognition, prestige, expanded social and business networks.”

“None of this is to diminish the good work a nonprofit may be doing, but the ends don’t always justify the means if it creates a perception of impropriety,” he added.

California’s political watchdog is stretched thin

Ethics and transparency advocates say California’s political regulator has not kept pace with ballooning campaign spending in the state and is woefully understaffed.

The FPPC is tasked with monitoring the finances and public disclosures of thousands of candidates and officeholders at state and local levels. Those who break the rules are hit with fines depending on the severity of the infraction.

The agency has a staff of about 100 lawyers, investigators and support staff to do this work. Multiple people who have spent time at the FPPC told The Bee the staff is not big enough to effectively do the job. The commission primarily opens inquiries in response to tips – and bigger investigations can often take years to complete.

“Everybody loves oversight unless they’re the ones being overseen,” said Schnur, who led the agency during the final year of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s term. “So it’s not surprising that legislators and governors tend not to give their watchdog enough resources to do the job.”

He said it’s easy for the agency to focus on lower-level infractions at the expense of more serious offenses or corruption.

“There’s so many minnows,” he said, “that it’s really easy to lose track of the whales.”

Schnur credited current chairman Adam Silver, saying he has “done better than most” at prioritizing high-level cases.

One of the biggest fines the agency leveled in 2025 was against Evan Low, a Democrat who served in the legislature for a decade. Low was fined $106,000 for concealing payments between his tech nonprofit and actor Alec Baldwin.

Low, who now works as president and CEO of the LGBTQ+ Victory Fund, settled the fine – but not from his personal assets.

He paid it using leftover campaign cash stashed in an account called “Evan Low for State Controller 2030.”

_____

©2026 The Sacramento Bee. Visit sacbee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments