Andreas Kluth: America's peacemaker-in-chief doth protest too much

Published in Op Eds

President Donald Trump still has seven-eighths of his second term left to leave his mark on the world as the “peacemaker” he promised to be in his inauguration speech — and thereby to bag that Nobel Peace Prize he so unsubtly keeps asking for. In the meantime, how about an interim assessment? Especially since he’s already offered his own.

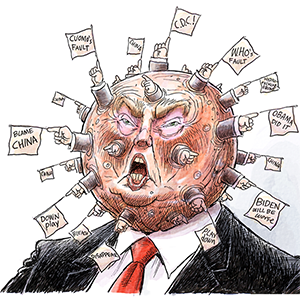

“We've been very successful in settling wars,” the president boasted the other day. “You have India, Pakistan, you have Rwanda and the Congo.” Trump seemed especially proud of pacifying that African conflict as he imagines it, what with those “pretty rough weapons like machetes, heads chopped off.” On he went: “Serbia, Kosovo, got that solved.” Ditto Armenia and Azerbaijan. He’s still working on the Middle East, Trump conceded, “but we’re doing pretty well on Gaza.”

What a remarkable riff. First, there was his boast’s contextual non sequitur: The president was ostensibly in that meeting to explain why he saw himself forced to get tough — sort of, maybe, soon — on his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. Awkwardly, Trump as candidate promised to end the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine in 24 hours. But here is Putin, six months after Trump’s oath of office, bombing Ukrainian cities harder than ever.

Trump presumably listed those other — and to most of his fans less familiar — hotspots to distract from that salient peacemaking failure. That makes them no less interesting.

His intervention in the recent stand-off between India and Pakistan should indeed count as an achievement.(1) By talking sense to New Delhi and Islamabad, the Trump team defused another clash between these two nuclear powers. What was notable at the time, though, was not that Washington mediated at all, but that it intervened later and more haphazardly than did previous American presidents in analogous crises. And Trump didn’t make peace in South Asia — he merely helped prevent two old adversaries from escalating in their latest round.

Trump can also take some credit — alongside the Qataris, who also mediated — for brokering a ceasefire in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where a rebel militia backed by Rwanda had been on a rampage, displacing millions. Last month, Rwanda and Congo reached a tentative truce in Washington. This month in Doha, the militia also signed. With luck, peace will ensue.

What interested Trump was probably the gold, cobalt, lithium and other minerals to be mined in the DRC. Beyond that, there’s scant evidence that he knows or cares much about Africa. (2) That may be why he didn’t mention one of the world’s worst wars: that in Sudan, which rages on not only unsolved but largely unaddressed.

The other successes Trump cited were fanciful. Armenia and Azerbaijan have indeed been inching toward a peace deal, but it looks fragile, and the U.S. (under both Trump and his predecessors) has been just one of several mediators, alongside the European Union and others. That applies equally to the frozen (but occasionally thawing) conflict between Serbia and Kosovo. There is no plausible rationale for calling these conflicts “solved,” by Trump or anybody.

What Trump’s examples have in common is that they’re peripheral conflicts, not in terms of human suffering but of geopolitical importance and media visibility. Unlike Israelis or Ukrainians, Kosovars and Congolese do not move poll numbers in the U.S., nor is America at risk of getting drawn into foreign quagmires on their account.

That’s what made Trump’s comment about Gaza so dissonant. Having entered office touting an apparent ceasefire, Trump is now a bystander as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, nominally his ally, does as he pleases: choking the Gaza Strip in ways that increasing numbers of scholars deem genocidal, or bombing Iran and now Syria.

In the Middle East, Trump is offering neither peace nor strength, only posing as if he were. Both the Israeli bombing of Syria and of a Catholic Church in Gaza caught Trump “off guard,” his press secretary admitted. Lacking control over “Bibi,” Trump instead keeps having to decide between looking feckless and joining in, as he did when the U.S. bombed Iran’s nuclear facilities. Sometimes his frustration shows, as when he complained that Israelis and Iranians “don’t know what the f*** they’re doing.” Other times he seems in denial, as when he claimed that he’s “doing pretty well in Gaza.”

Even when he conspicuously displays American might by bombing weaker adversaries, he doesn’t have much to show for it afterward. At great expense in valuable ordnance, he struck the Houthis in Yemen for a while because they were terrorizing shipping lanes. Then he declared victory and stopped. But the Houthis are still terrorizing, and the Red Sea is no closer to peace.

Then there’s that war in Ukraine. It’s the most consequential because the sovereignty of an entire nation is at stake (and thereby the international system as such), and because China is watching how the U.S. handles Russia’s aggression to war-game future scenarios in the Taiwan Strait.

Trump played this one wrong from the start. John Bolton, the third of Trump’s four National Security Advisors in his first term, told me that Trump believes that if he has a good relationship with a foreign leader, all will be well for their countries, “which is ridiculous.” He trusted in particular his personal chemistry with Putin. Instead, Bolton says, Putin “successfully manipulated him. That KGB training hasn’t gone away, until finally it does look humiliating for Trump.”

Because Putin made him look so impotent, Trump is now trying to change course — albeit with an as-yet unconvincing and arbitrary deadline of 50 days before new sanctions are to take effect, a deadline that Putin seems instead to view as a window to give Ukraine extra hell. What might happen if real peace negotiations ever begin is also unclear, since Trump has already given away Kyiv’s best chips, including its future membership in NATO and repossession of its lands occupied by Russia.

Trump is likely to fail in his stated ambition of becoming a peacemaker for many reasons. The historian Timothy Naftali looked at three successful mediations by American presidents in the 20th century: Teddy Roosevelt’s brokering of an end to the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 (which made him the first of four U.S. presidents to win a Nobel Peace Prize), John F. Kennedy’s deal to end the conflict between Indonesia and the Netherlands in 1962, and Jimmy Carter’s success in making peace between Egypt and Israel in 1978 (one of several achievements for which Carter later became the third president to be a Nobel laureate). (3)

One thing that Roosevelt, Kennedy and Carter had in common was credibility as honest brokers and neutral parties (even if Roosevelt at the outset seemed to favor the Russians, Kennedy the Indonesians, and Carter the Egyptians). Trump may appear as an honest broker in central Africa and South Asia (where he scored his wins). But in the wars that matter — Ukraine and the Middle East — Trump looks much too biased on behalf of Putin and Netanyahu.

Roosevelt, Kennedy and Carter also kept their peace efforts largely separate from domestic American politics. Trump, for his part, uses them as tools in his permanent campaign. And the three 20th-century presidents made peace for its own sake, not to extract material concessions for the U.S. Trump generally seems to get interested only when there’s a separate deal in it for him, as for minerals in Ukraine and the DRC.

The underlying problem is that Trump doesn’t understand his own slogan, Peace through Strength, which he borrowed from Ronald Reagan (who didn’t win a Nobel but arguably should have). Whether Trump Always Chickens Out or not, he is too wrapped up in his own ego, too limited by his short attention span and too used to thinking of governing as starring in a reality TV show.

When it came to peacemaking, Roosevelt, Kennedy, Carter, Reagan and some other presidents intuitively grasped the epiphany that eludes Trump: The world does not revolve around American presidents. If they want to change it for the better, they need to put the goal — peace — above themselves.

(1) Especially for Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who also became National Security Advisor just days before that crisis started.

(2) When a group of African leaders visited him the other day, the US president praised his Liberian counterpart for his language skills: “Such good English,” Trump said; “Where did you learn to speak so beautifully?” Liberia is an Anglophone country founded in the 19th century by freed and free-born American slaves.

(3) The other two presidential laureates offer fewer lessons for Trump. Woodrow Wilson won the prize for midwifing the League of Nations, whereas Trump is more likely to help bury its successor, the United Nations. Barack Obama won it early in his presidency, in what appeared to be a down payment for future achievements – a decision that seemed bizarre even at the time, even if Trump would now like the same favor.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering U.S. diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments