Art Institute of Chicago acquires Norman Rockwell's 'The Dugout,' his famous painting of the Cubs

Published in Entertainment News

CHICAGO — Norman Rockwell’s “The Dugout,” a classic portrait of slumped Cubs, dejected Cubs, defeated Cubs, a morose team resigned to an existential slog of failure, now hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. It was gifted to the museum by former Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner and his wife, Diana, who have had it hanging in their home for the past 19 years. It was installed on Tuesday morning across from Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.”

It’s not just the first Norman Rockwell painting in the entire collection of the Art Institute — and he painted 323 covers for the Saturday Evening Post between 1916 and 1963 — it’s probably the first major work in the museum’s collection that depicts a popular sport.

“When the Rauners reached out to see if we were interested, we were absolutely immediately interested,” said Sarah Kelly Oehler, the Art Institute’s chair and chief curator for arts of the Americas. “I had been thinking for years that it would be wonderful to get a Rockwell in our collection, and this, being Chicago, is the perfect painting.”

“The Dugout” is among the most indelible 20th century images of America’s pastime, painted back when it really still was America’s pastime, before faster-moving football and basketball leagues chipped away. It shows a dugout full of hangdog Cubs while a crowd behind them jeers relentlessly.

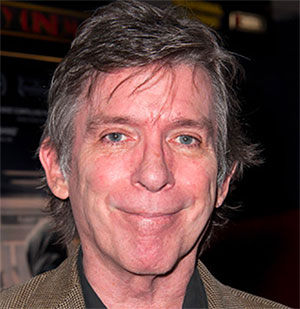

The Rauners bought the Rockwell via Christie’s in 2009 for $662,500. They bought it, Bruce Rauner said, “for two reasons. I am a longtime Cubs fan and followed them as a kid, but also I am a huge fan of Norman Rockwell, who is the most iconic of American painters. We really loved owning it. I didn’t necessarily even want to donate it — except after I was dead. But this seemed like a great time to say thank you to the people here.”

Plus, he said, since it was made in 1948, it’s mostly been in private collections.

“It’s such a community-focused painting,” said Diana Rauner, “that I felt more people should be seeing this, and it was a little weird to have it not be part of any community.”

Tom Ricketts, Chicago Cubs chairman, said in a statement: “It is fitting the Art Institute honor ‘The Dugout,’” particularly on the team’s 150th anniversary as a National League franchise. What he failed to mention is that this is also a portrait of the Chicago Cubs as a last-place team in 1948.

It practically oozes 64 wins and 90 losses.

In fact, even if you’ve never seen “The Dugout,” if you grew up on the North Side of Chicago, you’ve certainly felt it. Bruce Rauner definitely did. He was born near Wrigley Field in 1956 — yet another season during which the Cubs finished in last place. However, Rauner never really regarded the painting as sad. “It is about emotion and baseball is about emotion and the feelings (in the painting) are just part of competition.”

“I thought of the faces as beautiful,” Diana Rauner said. “We had this hanging in our home for a while, so we looked at it every day — those faces are really expressive.”

Easy for them to say.

Here’s what you’re looking at when you look at “The Dugout”: You’re looking at the Cubs early in their season, during an ugly doubleheader in Boston against the Boston Braves. You’re looking at, on that bench, from left, pitcher Bob Rush, manager Charlie Grimm and catcher Rube Walker. The player behind the sad batboy is pitcher Johnny Schmitz. And that very sad batboy was Frank McNulty, a Braves batboy who was coaxed into a Cubs uniform to pose for photos that became the painting.

You’re looking at, in those stands behind them, actual Boston fans who posed. The woman needling the Cubs, hands at her head, was the daughter of the Braves coach.

You’re looking at a doubleheader the Cubs dropped entirely.

You’re also looking at an image that helped cement the Cubs as the lovable losers of baseball for generations of fans, having been published when the Saturday Evening Post still had 3 million subscribers a week. That painting, when placed alongside A.J. Liebling’s infamous “Second City” series in the New Yorker just four years later, did nothing for Chicago’s growing midcentury reputation as a large but insecure cowtown.

“I think this is how Chicagoans see themselves,” Oehler said.

“They have a tremendous optimism but tend to grumble.” Indeed, she noted Rockwell’s work, which was often called sentimental by critics, and just as often overlooked for its influence and social issues, “helped define the way Americans thought of themselves.”

Typically, Rockwell created his Saturday Evening Post covers using oils, then the magazine would reproduce those oil paintings. This one, however, is an oil study by the artist. (The work reproduced for the “Dugout” cover was actually a rare watercolor, now hanging in The Illustrated Gallery outside Philadelphia.) Everyone in the image, Cubs, Braves and fans alike, agreed to pose for photographs, later used as studies for the painting. That’s how Rockwell worked.

“The Dugout” is also a good example of the growing willingness of major fine arts institutions to embrace commercial illustration, even when it crosses into pop culture. For decades, the Art Institute had rarely collected anything like a Norman Rockwell.

“It’s becoming more typical to see the barrier that long separated fine arts from applied arts growing more porous with big museums,” said Stephanie Plunkett, chief curator of the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. “Illustration is the people’s art in many ways, and while professional curators were once the main authority for what we should see, museums now are much more engaged in what the audience would like to see.

“Still, I wouldn’t call Rockwell really a sports guy. He painted baseball, football, some golf. He lived in Massachusetts the last 25 years of his life, so he would have been a Red Sox guy. But what he really loved was the underdog, even from the earliest days of his career. He always possessed a particular empathy when it came to the losers.”

Indeed, compared with the realistically creased faces and hangdog stares of the Cubs, the Boston fans behind them are closer to grotesques, an inhuman crush of caricatures.

You might even say that Rockwell was unintentionally trolling the Cubs in 1948. Later that season, at Ebbets Field in New York City, he had a photographer capture the Brooklyn Dodgers playing the Cubs for a spring 1949 cover. The Cubs lost that game, too. Luckily, Rockwell returned the next day to shoot the Dodgers and the Pittsburgh Pirates, which became the study Rockwell used for an even more famous work, “Game Called Because of Rain (Tough Call),” an image of three umpires evaluating stray drops of precipitation. It hangs today in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

If there is a sunny side to “The Dugout,” it’s that the Cubs were not the absolute worst team in Major League Baseball in 1948. That distinction went to the Chicago White Sox, who finished the American League season in the basement, dead last with 101 losses.

Rockwell didn’t bother to paint them at all.

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments