Florida is reshaping higher education. Other states are watching

Published in News & Features

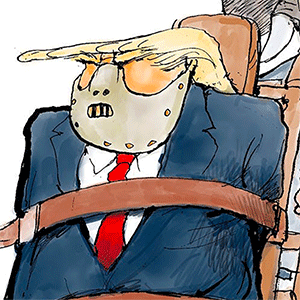

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis often says that Florida is the best state in the country for higher education.

It’s been ranked No. 1 for higher education by U.S. News & World Report for nearly a decade, and the University of Florida was tied as the seventh-ranked top public university this year. Other schools, like the University of South Florida and Florida State University, rose in the ranks, too.

The same schools that produce successful students have also drawn heavy scrutiny, from the Board of Governors blocking a candidate in UF’s presidential search last summer to New College of Florida’s political makeover and hefty spending habits.

But Florida isn’t only drawing critics. It’s drawing copycats.

The state has been at the forefront of the push to eliminate campus diversity initiatives, create schools focused on Western thought and restrict student activism on campuses. It even established a college accrediting body this summer that includes university systems in the Carolinas, Georgia, Texas and Tennessee.

DeSantis receives more national coverage than other Republican governors, which can thrust Florida into the spotlight, even if the state isn’t setting policy trends, said Tyler Coward, the lead counsel for government affairs at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a pro-free speech group.

Florida’s higher education policy can also be particularly aggressive because elected officials have term limits, said Antonio Ingram, an attorney with the Legal Defense Fund, a nonprofit that fights for racial justice. They can pursue aggressive policy agendas because they don’t need to face voters cycle after cycle, he said.

“I think Florida may not be perceived as conservative as places like Alabama and Texas, but once Florida does things, they ripple,” Ingram said. “I think other institutions get emboldened. Like, ‘Florida did it. Why can’t we?’”

More change could be coming. Florida’s legislative session began this week, which means lawmakers will start to consider bills that would limit the governor’s influence on presidential searches, allow guns on campus and rename campus roads in honor of the late conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

Here’s how some states have already followed Florida’s lead in higher education policy.

Diversity, equity and inclusion bans

Florida’s 2022 Individual Freedom Act, also known as the Stop Woke act, was one of the first pieces of legislation to try to restrict campus conversations about race and push back against critical race theory, the idea that racism is systemic. The legislation prohibits any teaching that would make someone feel “guilt, anguish or other psychological distress” due to their race.

The legislators who wrote the bill were likely inspired by a controversial executive order that President Donald Trump passed in his first term, Ingram said. Trump’s order banned training for federal employees and contractors that included topics like systemic racism. Former President Joe Biden repealed it early in his term.

After many challenges, a federal judge blocked the parts of the Florida law that involve higher education and the workplace.

But DeSantis signed a 2023 bill that prohibits colleges from spending state or federal funds on diversity-related projects unless required by federal law. And the state overhauled general education classes, weeding out hundreds that focused on race and gender.

“I think that it’s a model of good governance, it’s a model of seriousness in terms of the policies towards higher education,” said Mark Schneider, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

“Because it’s big, it’s visible, it’s well-governed, it does the right thing, people are going to look to it.”

Texas adopted similar language in two bills in 2023, and so did Alabama in 2024.

Alabama’s legislation restricts colleges and universities (and groups within them) from holding events related to diversity, equity and inclusion. It also prohibits the teaching of “divisive concepts,” including the idea that individuals can have subconscious racial biases.

The bill took Florida’s idea and expanded on it, Ingram said, to put restrictions on extracurricular student events. And Alabama follows Florida’s lead often, he said.

“Florida and Alabama are in the same Court of Appeals jurisdiction,” he said. “I think it’s not a coincidence that once Florida passes laws that get upheld in court, that other states in that federal system are like, ‘Well, the law is on our side because Florida opened up the door.’”

Higher education boards in more distant states authored similar policies, too.

The University of North Carolina Board of Governors banned offices and staff related to diversity, equity and inclusion and enacted a policy of “institutional neutrality.” UNC-Chapel Hill, the state’s flagship university, closed more than half a dozen related offices, cut nearly 60 positions and redirected millions of dollars.

And Ohio’s 2025 sweeping higher education law, intended to remove liberal bias, also requires colleges and universities to end diversity, equity and inclusion work.

Student activity restrictions

In 2024, DeSantis ordered the state highway patrol to help crack down on pro-Palestinian protests. Universities had let themselves become “overrun” with encampments, he said, adding that protesters were “spouting nonsense.”

Some state universities enacted campus-wide restrictions on student activity, some of which critics say unfairly target left-wing organizers. At USF, a new policy prohibits protests past 5 p.m., restricts the wearing of masks to conceal identities and requires approval for campus events and dispersing literature.

A handful of schools across the country, particularly those with students who led pro-Palestine encampments, tightened guidelines on student activism and events.

Carnegie Mellon University, a private university in Pittsburgh, banned encampments and required registration for “formal advocacy events.” The UNC Board of Governors has placed restrictions on protests. Last year, they approved new system-wide guidelines, which include providing a 24-hour notice when a large group intends to gather.

In Texas, a state law passed last year requires students to get permission from their universities before bringing guest speakers to campus.

“I think the backlash we’re seeing in Florida and other states is because (universities and governments) are trying to stifle what they deem to be hotbeds of political engagement that may not align with the current political power systems in those states,” Ingram said.

Classical education centers

UF’s Hamilton School for Classical and Civic Education was established in 2022 with state funding.

It is one of many universities to create schools focused on civics education and Western philosophy, which tend to employ conservative faculty. Florida is also home to New College, a small liberal arts college that DeSantis overhauled a few years ago to turn into a conservative civics college.

Florida wasn’t the first to start a civics school. But, Ingram said, the state doesn’t need to be the only player or initial spark to influence other policymakers.

Ohio last year passed a bill that created five civics centers at state universities, including Ohio State. The most recent state budget allocates more decision-making power to the centers, including advising lawmakers on curricula for K-12 schools.

In North Carolina, UNC’s School of Civic Life and Leadership opened in 2024. It’s an effort to bring more right-of-center views to campus, former trustees chairperson Dave Boliek told Fox News.

Classical education centers could embrace a wide variety of faculty and student opinions, Coward said. But how they’ll actually work is unclear, he said.

“(Civics schools) are certainly something that a lot of people, a lot of politicians and conservative political folks, like to latch on to,” said Holden Thorp, a former chancellor of UNC-Chapel Hill. “I usually tell people on these campuses who object to these things not to focus on it because it ends up being a really small percentage of the students that end up doing things there.”

Nevertheless, UF has pushed resources toward Hamilton. The school recently received a $5.5 million gift, and the university broke ground on its Infirmary, set to be Hamilton’s new home. Former Florida Supreme Court Justice Charles Canady left the bench to become the school’s director.

Schneider and Coward both said DeSantis’ voice represents many Americans in red states who are unsatisfied with the country’s higher education system.

In a recent Pew Research Center poll, 77% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say higher education is going in the wrong direction, compared to 65% of Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents.

Florida tapped into something much bigger than itself, Coward said.

_____

©2026 Tampa Bay Times. Visit tampabay.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments