Man known as 'Starved Rock Killer,' who long fought for his freedom, dies of cancer

Published in News & Features

CHICAGO — Despite his persistent claims of innocence, Chester Weger lived six decades in prison after confessing to the haunting 1960 Starved Rock State Park murders of three suburban Chicago women who were attacked during a hike in broad daylight.

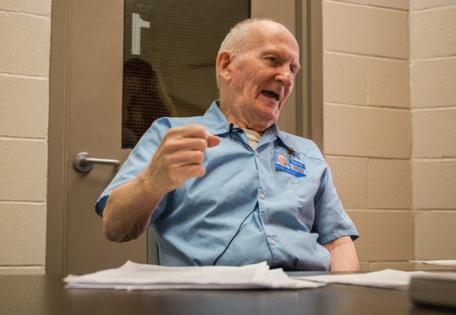

Dubbed the infamous “Starved Rock Killer,” Weger finally won his freedom more than five years ago and lived a quiet life while making occasional appearances in court to try to overturn his conviction. A LaSalle County judge had denied Weger’s post-conviction petition June 18.

Days later, on Sunday, 86-year-old Weger died of cancer, still with the stigma of having a murder conviction staining his record. He died in Kansas City, surrounded by his family, his attorney Andy Hale said.

“Chester fought until the end to clear his name,” Hale said. “We are deeply saddened that Chester’s legacy is marred by this unjust conviction.”

Hale, who described Weger as “humble, generous and kind,” pledged to continue his efforts to clear his client’s name. Hale said, “Chester has been such an inspiration to me and it was an honor to represent him.”

Weger was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for the fatal beating of Lillian Oetting, 50, in March 1960 at the scenic park near Utica. Her remains were found in St. Louis Canyon along with the brutalized bodies of Frances Murphy, 47, and Mildred Lindquist, 50.

The three friends, all from Riverside, were on a short vacation to escape the winter doldrums when, within hours of their arrival, they were attacked during a hike in the canyon, a popular attraction framed by a scenic waterfall and towering canyon walls.

Prosecutors, citing Weger’s life sentence, opted against trying him in the other two women’s deaths and an unrelated 1959 rape in a nearby state park that Weger also denied committing.

For months after the killings, police followed Weger, a young lodge dishwasher who had fished and hiked in the park most of his life. Investigators had focused on Weger early on after lodge employees reported seeing scratches on his face, but he passed several lie-detector tests. Authorities believed twine used to bind the women came from the lodge kitchen.

Investigators interviewed him several times, including during an all-night interrogation. He confessed early on Nov. 17, 1960.

Prosecutors later argued that Weger killed the women with a frozen tree branch during a botched robbery attempt. They said Weger knew things only the killer could have known, such as the fact that a red-and-white airplane flew over the canyon the day of the murders. Detectives later confirmed that detail by checking the flight logs at a local airport.

But Weger has long maintained that investigators fed him those details. He recanted his confession by the time of his trial. His attorneys have argued his confession was coerced, a product of police misconduct.

More than six decades later, conspiracy theories and morbid fascination still surround the case. The murders occurred before modern DNA testing and other forensic advances, and Weger has offered various alibis over the years, including during a 2016 prison interview with the Tribune.

His attorneys, Hale and Celeste Stack, continued post-conviction efforts, arguing the Chicago mob was likely behind the murders. The defense presented several witnesses, including forensic experts who testified that a lone hair found at the scene did not belong to Weger.

The Illinois Prisoner Review Board had denied Weger’s parole requests for decades. The panel finally allowed for his eventual release in early 2020, citing his age and decades of incarceration, after the trial’s lead prosecutor, Anthony Raccuglia, who long urged the board to keep Weger behind bars, died months earlier at 85.

When Weger finally emerged from the Pinckneyville Correctional Center gates in southern Illinois, he was a balding grandfather with dentures and a list of ailments that include asthma and rheumatoid arthritis. That day, he told the Tribune he would continue his fight to clear his name.

“They ruined my life,” he said minutes after leaving prison in February 2020. “(They) locked me up for 60 years for something I’ve never done.”

Several of the victims’ grandchildren, still convinced of his guilt, opposed his release at the time. They said the decades-old crime reverberates still.

“The legacy of this murder has impacted all of the generations alive today,” Kathy Etz, one of Murphy’s granddaughters, told the Tribune in 2020.

_____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments