No degree, no job? Tighter labor market leaves many with fewer options

Published in Business News

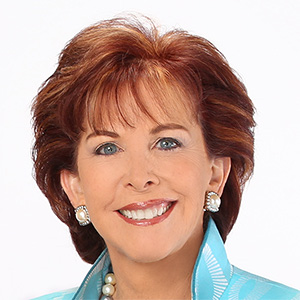

Cheryl Wilson’s résumé is near perfect.

She has worked all her life, notching decades of experience at back-to-back corporate jobs that often tapped her to train new hires.

But after a software company laid her off two years ago, the 64-year-old has struggled to land a new job for the first time in her career.

Because for all her experience, there’s one missing element from Wilson’s résumé: a college degree.

The labor market slowed this year as economic uncertainty made employers hesitant to hire, a reversal from the worker-friendly Great Resignation period a few years ago. The loss of employee power has hit new college graduates hardest, with their unemployment rate now outpacing overall unemployment for the first time in decades.

Now, with year-end layoffs in full swing and the latest jobs reports showing continued sluggishness, jobseekers are facing even more competition.

“At this point in my life, I’m afraid I’m not going to ever get another job,” said Wilson, of Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota. “I know a lot of people are laid off. Everyone is looking for jobs.”

A recent survey found many Americans don’t believe a college degree is worth the cost yet the unemployment rate for college graduates as a whole remains lower than for those without a degree. And as employers tighten up hiring criteria in the loosening labor market, it’s becoming even harder for the roughly 60% of Americans without a degree to land a job.

“It feels like the landscape is incredibly competitive. It feels like individuals who have those degrees are applying for a wider variety of positions, including entry-level positions,” said Becca Lopez, vice president of career education and employment services at workforce nonprofit Avivo. “And so it can feel to our jobseekers like there maybe isn’t room for them in this labor market.”

The September jobs report, released Nov. 20 after a delay during the federal government shutdown, showed a 2.8% unemployment rate for degree-holders aged 25 and older. For high school graduates without a degree, that number was 4.2% — slightly under the national unemployment rate.

Minnesota in September had a lower unemployment rate overall, at 3.7%, and a lower rate for college graduates, at 2.1%, according to data from the state Department of Employment and Economic Development. But high school graduates without degrees had a higher unemployment rate, at 4.8%.

Faced with a historic worker shortage coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic, major employers in Minnesota and across the country shifted to “skills-based hiring” that values experience rather than educational attainment.

Results have been limited: Less than 40% of employers that removed degree requirements in the past decade have significantly changed their hiring practices, according to a report last year from the Burning Glass Institute and Harvard Business School.

Though the college wage premium has stagnated in the past 20 years, according to research from the San Francisco Fed, college-educated workers still earn about 75% more than those without degrees.

“I think that for most higher-paying jobs, it’s still the case that a four-year degree is just the cutoff,” said Bill Baldus, career center director at Metropolitan State University. “Can people get great jobs without one? Absolutely. But you’re going to be a much stronger candidate with a degree.”

Students at the St. Paul university are either working or looking for work while pursuing their degree, Baldus said. The school offers resources including a course on navigating the job market in partnership with local employers.

Faculty have started to recognize the need to aid in closing the skills gap for students aiming to become “first-generation professionals,” said career counselor Rachel Nihart.

“There’s frustrations of, ‘I don’t have a degree. How do I get into this market?’ ” she said. “ ‘I don’t know what working with Microsoft Teams looks like. I don’t know what working with Excel looks like.’ ”

Nihart said more students are visiting her office as the job market tightens, and more are still in contact six months after their initial visit. Many are applying for jobs and not hearing back, she said.

Kila Seki, 23, has worked in retail and other customer-facing roles since she was a teenager. When she pursued higher-paying work, she said, she faced rejection after rejection.

This spring, Seki transferred from a community college to Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, Minnesota, and expects to graduate in about a year with a bachelor’s degree in marketing management.

“The turning point for me was that talent and hard work is not always going to win, so you need credentials,” she said. “I knew that I wanted a real opportunity.”

As a teenager in Alabama, Wilson was on track to study fashion and design. Then she got pregnant.

Her mother offered to care for the baby while she pursued her degree, but because she had already raised 10 children and one grandchild, Wilson said no.

“I said, ‘This is my responsibility, so I won’t. I can’t let you do that,’” she said.

Decades later, Wilson still wants to work full time. She’s taking an online computer skills course through Minneapolis-based nonprofit Hired and plans to seek help brushing up her résumé and practicing interviewing.

She hopes prospective employers can look past what’s missing from her résumé, and those of others without degrees, and see what’s there — experience, hard work, an eagerness to learn.

“College is really important, but that wasn’t in the cards for me,” Wilson said. “But I have worked. I’ve paid my taxes. Just give us a chance to prove ourselves.”

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments